A living document on how to juggle these damned things.

Updated March 19, 2025.

What’s a KEM?

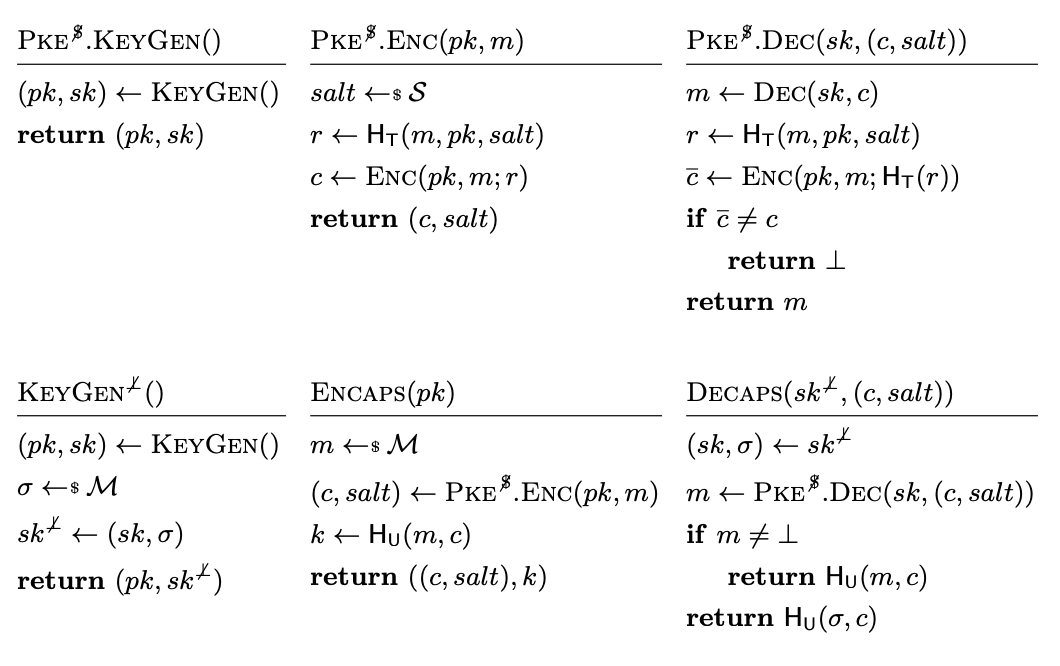

A KEM is a Key Encapsulation Mechanism, a cryptographic primitive that has a

KeyGen() algorithm, an Encaps() algorithm, and a Decaps()

algorithm. KeyGen produces a (decaps_key, encaps_key)

keypair. Encaps(encaps_key) uses an encapsulation key (similar to an

asymmetric public key) to compute and return a shared secret and the

encrypted ciphertext encapsulation of that shared secret (often called ct

or enc). Decaps(ct, decaps_key) takes the encapsulated shared secret

ciphertext and the decapsulation key (similar to an asymmetric secret key) to

re-construct the shared secret.

KEM diagram from FIPS 203

KEM diagram from FIPS 203

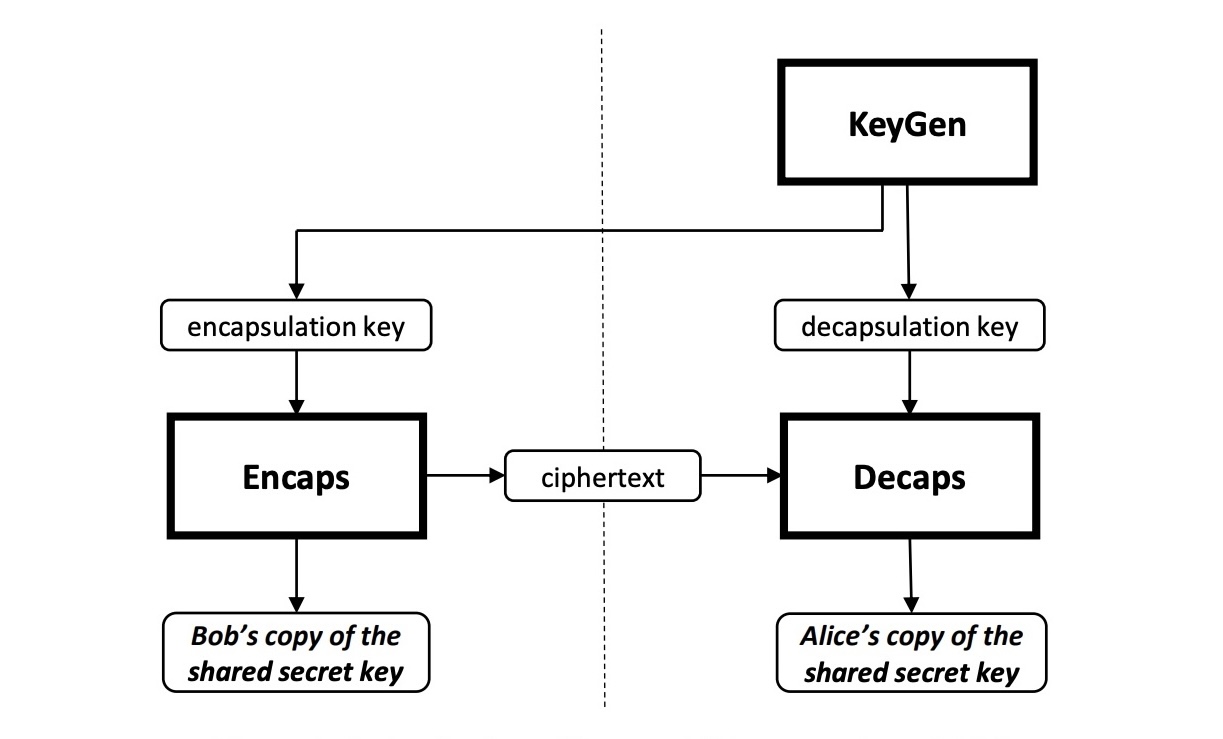

In general, cryptographic primitives are designed to fulfill a particular

security property when instantiated correctly, and that property is defined

as being able to beat an adversary modeled with certain abilities within a

security game. For digital signatures, there is usually an unforgeability

property under chosen message attack (EUF-CMA); for KEMs, the property is

indistinguishability under chosen ciphertext attack (IND-CCA). Informally

this means that the computed shared secret is indistinguishable from random

against an adversary who can decapsulate maliciously constructed ciphertexts,

but who doesn’t have direct access to the decapsulation key.

IND-CCA experiment for KEMs, from “Keeping Up with the KEMs”

IND-CCA experiment for KEMs, from “Keeping Up with the KEMs”

KEMs have become ‘all the rage’ recently (not because they are sexy or special, they just seem to be the best we’ve got in a post-quantum world). In the shadow of a cryptographically-relevant quantum computer that can break our Diffie-Hellman’s and elliptic curve-based constructions in ~polynomial time, including stuff that’s been hoovered up and stored for a later day when those quantum computers come online (Store and Decrypt Later), there’s been movement to migrate cryptography protocols off of Diffie-Hellman onto primitives like KEMs, because they enable things like key establishment, but base their security on quantum-resistant problems such as Module Learning-with-Errors.

However. KEMs are not DH, and protocols that were originally designed based

on the properties (formal and informal) of Diffie-Hellman are now trying to

swap them out for KEMs or hybridize them with KEMs. KEMs generally are

designed to fulfill IND-CCA and IND-CCA only, and some designs have been

changed to simplify and make clearer IND-CCA security proofs and to improve

performance, but that also resulted in the removal of some of the other

security properties that make them trickier to just use without caveats.

Re-encapsulation attacks

As coined by Cremers et al and explored by the

Cryspen team, re-encapsulation attacks exploit the fact

that some KEMs allow the decapsulation of a ciphertext to an output key k and

then can produce a second ciphertext for a different public key that

decapsulates to the same k. Re-encapsulation attacks in protocols, often

known as an unknown-key-share attack, result in two parties computing the

same key despite disagreeing on their respective partners. This doesn’t sound

great, but is completely allowed under the IND-CCA security definition! To

avoid these sorts of attacks, we need to know more about a KEM than just that

it’s an IND-CCA-secure KEM: we need to know how it binds its shared secrets

to encapsulation keys and ciphertexts. This is a thing we didn’t need to

think about with Diffie-Hellman, as it was only in weird cases (small-order

points, ‘non-contributory behavior’, etc) that

Diffie-Hellman public keys were not tightly bound to the shared secret

resulting from the computation, and there was no ciphertext to juggle either.

Binding properties

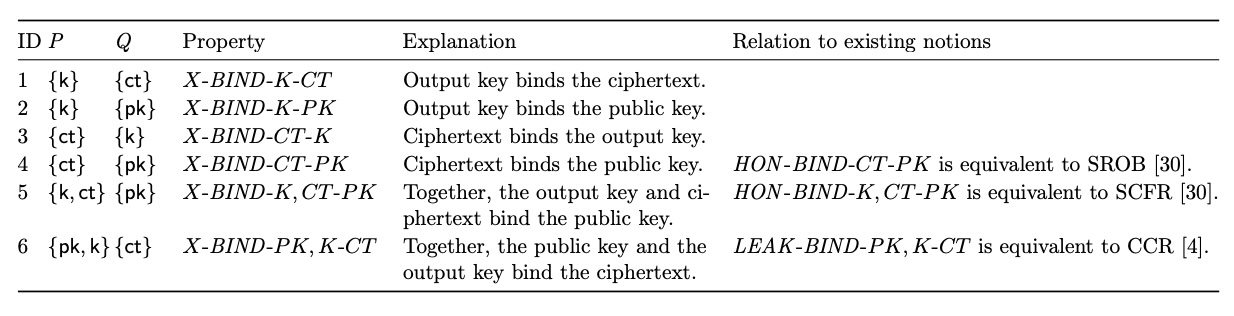

Cremers, Dax, and Medinger formalized these notions of ‘binding’ properties for KEMs and explored their relations to similar notions like ‘robustness’ and ‘contributivity’ in the literature, including describing a spectrum of adversaries with different capabilities, how these notions relate (or imply) each other, and checked them via symbolic analysis with Tamarin. For a value to ‘bind’ another value, such as a shared secret K binding an encapsulation key PK, is to uniquely determine it; more formally, “P binds Q” if, for fixed instances of P, there are no collisions in the instances of Q.

The generic binding property instantiations X-BIND-P-Q before choosing X ∈ {HON , LEAK, MAL} from “Keeping Up with the KEMs”

The generic binding property instantiations X-BIND-P-Q before choosing X ∈ {HON , LEAK, MAL} from “Keeping Up with the KEMs”

There are different security models of adversaries for these properties:

honest (HON), leak (LEAK), and malicious (MAL). Honest variants involve

everyone behaving themselves, such that the involved key pairs are output by

KeyGen() and not accessible by the adversary, but the adversary has access

to a Decaps() oracle. Leakage variants have honestly-generated key pairs

leaked to the adversary. Finally, in malicious variants, the adversary can

create the key pairs any way they like in addition to the key generation, so

they can do…a lot. Ideally, our KEMs would be resistant to such

adversaries, so these MAL-BIND-P-Q properties are attractive.

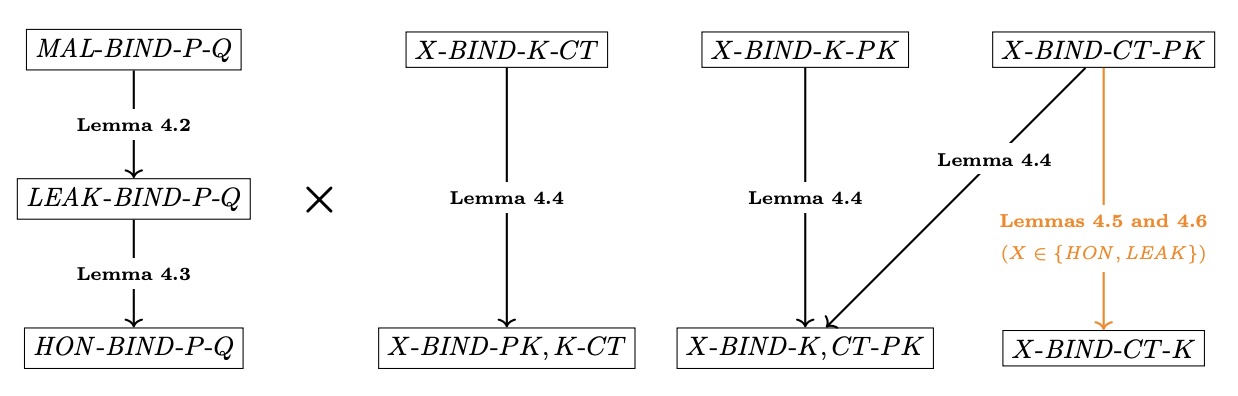

General hierarchy of binding properties for KEMs from “Keeping Up with the KEMs” (NB: implicit rejection KEMs have a restricted hierarchy)

General hierarchy of binding properties for KEMs from “Keeping Up with the KEMs” (NB: implicit rejection KEMs have a restricted hierarchy)

Some of the big takeaways here are that we like MAL-BIND-K-CT and

MAL-BIND-K-PK properties in our KEMs:

-

A

MAL-BIND-K-PK-secure KEM means that the KEM’s shared secret (K) binds to the encapsulation key (PK) used to compute it, even against a malicious adversary that has access to leaked key material and is capable of manufacturing maliciously-generated keypairs. This strong binding to the encapsulation key protects broadly against re-encapsulation attacks because different parties (as identified by their public key) cannot be coerced into deriving the same key. -

A

MAL-BIND-K-CT-secure KEM means that the KEM’s shared secret (K) binds to the encapsulated shared secret ciphertext (CT), even against a malicious adversary that has access to leaked key material and is capable of manufacturing maliciously-generated keypairs. This strong binding to the ciphertext protects broadly against re-encapsulation attacks so that two different ciphertexts cannot decapsulate to the same shared secret K.

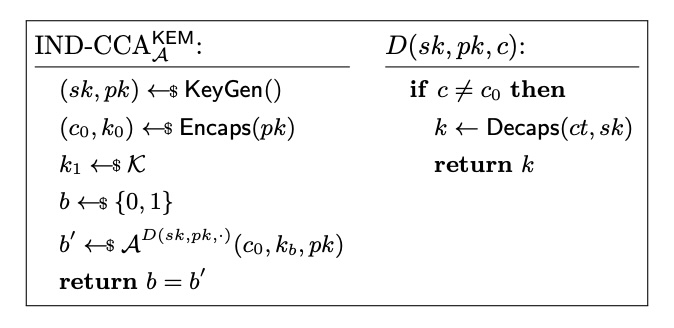

Implicit rejection

Digging even deeper, a lot of popular KEMs are implicitly rejecting, as a

result of their particular flavor of applying the Fujisaki-Okamoto (FO)

transform. The FO transform takes a public key encryption (PKE) scheme secure

under chosen-plaintext attack (IND-CPA) and turns it into an IND-CCA KEM

scheme. Implicitly rejecting KEMs always return a value, even if the PKE

decryption step inside Decaps() fails or returns an unexpected value. This

design means that Decaps() always returns a pseudorandom value, even if

decryption fails. This is hopefully safer to use in higher-level protocols

that may or may not check the decapsulation value. Because of

this implicit rejection design, there are fewer binding properties available

to such KEMs, period, and this generally eliminates their ciphertexts alone

binding to public keys or shared secrets: any ciphertext will be accepted,

and these will almost certainly decapsulate to different shared secrets. This

means that implicitly rejecting KEMS cannot be X-BIND-CT-K-secure or

X-BIND-CT-PK-secure for any of the binding adversary variants, and we are

only possibly left with the subset of binding properties below.

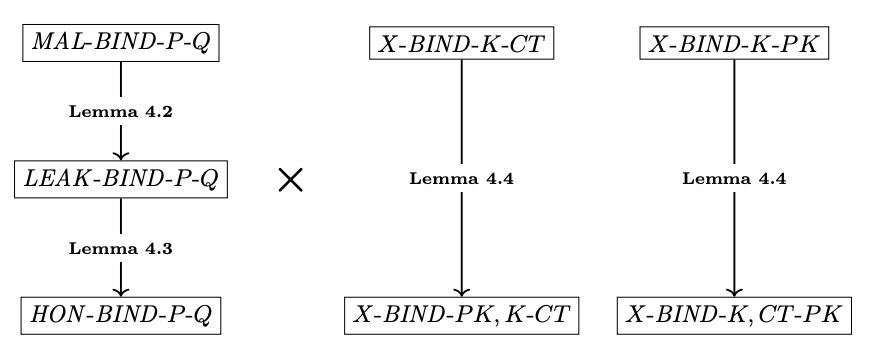

Restricted hierarchy of binding properties for implicitly-rejecting KEMs from “Keeping Up with the KEMs”

Restricted hierarchy of binding properties for implicitly-rejecting KEMs from “Keeping Up with the KEMs”

ML-KEM

Updated September 2024

Per the analysis of the final standard FIPS 203 in Sophie

Schmieg’s “Unbindable Kemmy Schmidt”, a strictly compliant

instantiation of ML-KEM is LEAK-BIND-K-PK-secure

andLEAK-BIND-K-CT-secure, but not MAL-BIND-K-PK-secure nor

MAL-BIND-K-CT-secure (although keep reading for caveats). This means that

the computed shared secret binds to the encapsulation key used to compute it

against a malicious adversary that has access to leaked, honestly-generated

key material but is not capable of manufacturing maliciously generated

keypairs. This binding to the encapsulation key broadly protects against

re-encapsulation attacks but not completely.

This step down from MAL security and vulnerability to the Kemmy

Schmidt attacks is due to the ‘expanded’ key format of ML-KEM

as specified in FIPS 203: the K-PKE PK hash is stored in the

decapsulation key format instead of being re-computed from the K-PKE secret

key. A MAL attacker can replace this K-PKE PK hash to trick the

decapsulator into calculating the same K for a different CT, therefore

violating the MAL-BIND-K-CT and MAL-BIND-K-PK properties. A MAL

attacker can also mess with the z FO-transform rejection value that is

cached in the expanded decapsulation key format, which can be the same as the

z in another key pair, and when the rejection value of K is returned, it

will match another K for different keypair, violating the MAL-BIND-K-PK

property.

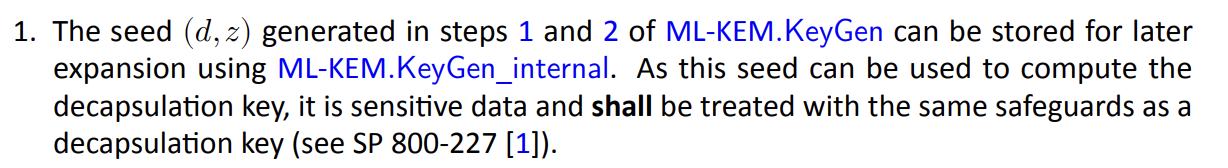

Luckily, before the standard was finalized, NIST listened to feedback about

some of these attacks and officially supported storing ML-KEM keys as two

seeds, the K-PKE seed d, and the FO-transform rejection value z:

FIPS 203 ML-KEM seed format for keys

FIPS 203 ML-KEM seed format for keys

This is functionally one 64-byte value, but according to the standard, this

is not a single 64-byte sampled value, but two 32-byte sampled values that

together make up the decapsulation key seed. Unfortunately, implementing this

format is not required, merely optional; therefore, one may have a

compliant instantiation of ML-KEM according to FIPS 203, which would be only

LEAK-BIND-K-CT-secure, vs another compliant instantiation of ML-KEM, that

only uses the (d, z) decapsulation key seed format, which is

MAL-BIND-K-CT-secure. 🙃

Using ML-KEM keys in this manner in practice protects against the first Kemmy

Schmidt attack above, but it does not protect against the second. It would be

nice to have a single 32-byte seed that

could be expanded in a compliant way into both d and z, but alas NIST

said no. If that were allowed, it would have

mitigated the MAL-BIND-K-CTand MAL-BIND-K-PK Kemmy Schmidt attacks

completely.

The (d, z) seed format is a fully FIPS-compliant way to store and use

ML-KEM, and I recommend using it in practice and plan to do so myself. To get

close to MAL-BIND-K-CT security with this format, the keypair _MUST_be

validated as well-formed via the ‘key pair check’ in section 7.1 - this

regenerates the expanded decapsulation key format and encapsulation key from

the seed format and checks that they match. This does have performance

implications.

ML-KEM is also LEAK-BIND-K,PK-CT-secure (ciphertext collision-resistant,

CCR). This means that the computed shared secret and the

encapsulation key together bind the ciphertext. Since ML-KEM is

MAL-BIND-K-PK-secure, given a shared secret K, we know it uniquely binds to

a PK, and because together K and PK uniquely bind to a CT, that means we get

LEAK-BIND-K-CT for ML-KEM, but not MAL-BIND-K-CT. This is formalized by

corollary A.8 in keeping-up-with-the-kems.

Once upon a time, there was Kyber before it was changed to not hash in the

ciphertext anymore. Kyber, as defined in version 3.02 of the NIST PQC

submission, hashed in the ciphertext into the derivation of the

shared secret and thus was MAL-BIND-K-CT as well as MAL-BIND-K-PK. This

was removed as Kyber transformed into ML-KEM, ostensibly to get the speedup

by avoiding hashing the large ciphertext while also making the IND-CCA proofs

of security simpler because that was the security goal at the time. Alas.

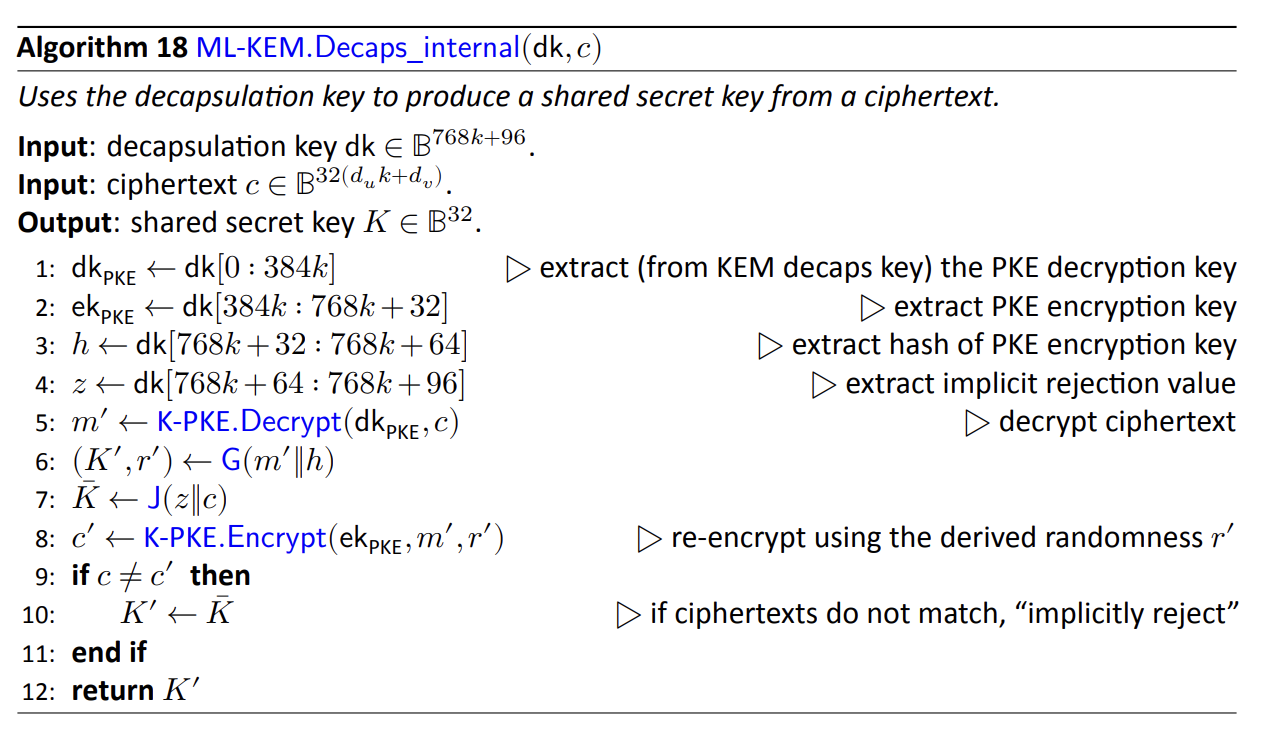

ML-KEM (and Kyber and some others) are implicitly rejecting KEMs. In ML-KEM,

the implicit rejection value is derived from randomness (part of the

decapsulation key) and the ciphertext (which is ostensibly

attacker-controlled). Yes, I am aware of the irony that the ciphertext is

bound by the implicit rejection ‘key’ but not the real shared secret. 💀 This

means that ML-KEM cannot be X-BIND-CT-K-secure or X-BIND-CT-PK-secure for

any of the binding adversary variants, and we are restricted to the smaller

set of binding properties for implicitly rejecting KEMs.

ML-KEM.Decaps_internal from FIPS 203, demonstrating implicit rejection

ML-KEM.Decaps_internal from FIPS 203, demonstrating implicit rejection

So to sum up, straight-up ML-KEM is LEAK-BIND-K-PK, LEAK-BIND-K,CT-PK,

LEAK-BIND-K,PK-CT, and LEAK-BIND-K-CT-secure, but not any flavor of

X-BIND-CT-K or X-BIND-CT-PK-secure. Using the (d, z) format of the

decapsulation keys and validating keypairs mitigates attacks such that

MAL-BIND-K-CT can be achieved…if you don’t fuck it up. 🫠

How do I hold it?

If I’m using ML-KEM in a protocol, in general, because it lacks

MAL-BIND-K-CT and MAL-BIND-K-PK security, I would make sure to commit to

the encapsulated shared secret ciphertext (CT) and encapsulation key (PK)

along with the decapsulated shared secret, either in the final protocol KDF

or something similar. TLS 1.3 commits to basically everything

in the handshake transcript as part of its key schedule, so they are already

doing this ‘for free.’ Apple’s PQ3 upgrade to iMessage includes

the ML-KEM ciphertext and encapsulation key in the label field of the

HKDF-Expand() call in its KDFRKCK KDF function, along with a lot of other

transcript stuff. In general, if you can afford it, I would hash in / commit

to all public data in the protocol transcript, including the encapsulation

keys - It can really save your ass.

Unless you write a security proof showing otherwise, the ML-KEM shared

secret does not bind to the ciphertext nor against adversaries that

maliciously twiddle key material, so I would recommend hashing it into your

KDF or equivalent along with the shared secret. Otherwise, there is a burden

of proof to demonstrate security against MAL adversaries.

To get close to MAL-BIND-K-CT security with the compliant seed format, the keypair MUST_be validated as well-formed - I recommend it. You may be able to skip including the CT in your external KDF if you do. Since MAL-BIND-K-PK is not achievable in a compliant way, I _strongly recommend including the PK (encapsulation key) in your KDF.

Classic McEliece

Classic McEliece is another PQ-secure KEM that is built on code-based cryptography (instead of lattices, like ML-KEM or Kyber). It is a fourth-round candidate in NIST’s PQC KEM competition, a proposed ISO standard, and the general McEliece public-key encryption design has a long and robust history behind it.

Classic McEliece, as specified in the NIST

submission, is MAL-BIND-K-CT-secure and

MAL-BIND-PK,K-CT-secure. This means you can use the shared secret output

without also committing to the encapsulated shared secret ciphertext. But

that’s it. Classic McEliece lacks any binding to the encapsulation key (PK)

in any of the adversary security models, as the underlying public key

encryption scheme allows a ciphertext CT to decrypt to the plaintext message

under any decryption key, not just the decryption key

associated with the public encryption key used to generate the

ciphertext. Since Classic McEliece derives the KEM shared secret only from

the ciphertext CT and the randomness (message), and the underlying PKE allows

us to generate the same shared secret K from multiple ciphertexts for any key

pair, Classic McEliece is not HON-BIND-K-PK or any other variant thereof.

Since Classic McEliece is also an implicitly rejecting KEM, it lacks the

X-BIND-CT-PK and X-BIND-CT-K properties too.

Classic McEliece from Anonymous, Robust Post-Quantum Public Key Encryption

Classic McEliece from Anonymous, Robust Post-Quantum Public Key Encryption

Therefore Classic McEliece is MAL-BIND-K-CT-secure and

MAL-BIND-PK,K-CT-secure, but not any flavor of X-BIND-CT-K,

X-BIND-CT-PK, X-BIND-K-PK, or X-BIND-K,CT-PK -secure.

How do I hold it?

You MUST commit to the Classic McEliece public encapsulation key (PK) as well as the derived shared secret K in your KDF or equivalent. This may be quite annoying as Classic McEliece encapsulation keys are much larger than, say, ML-KEM encapsulation keys, and hashing them or including them as inputs to your KDF may be computationally expensive.

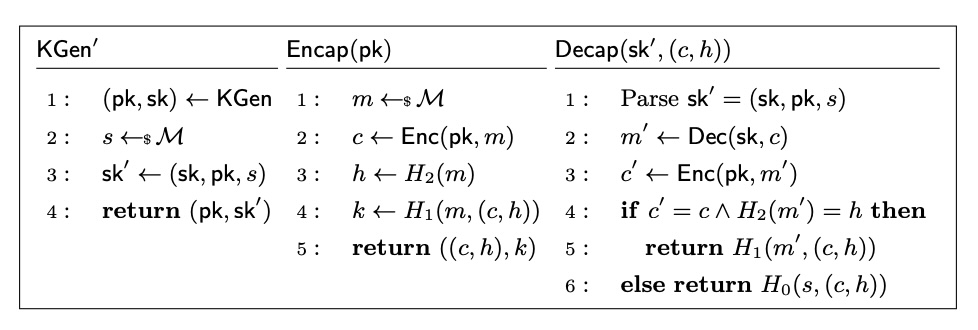

FrodoKEM

FrodoKEM is another implicitly rejecting PQ KEM based on lattices, but it relies on the learning-with-errors problem instead of the module-LWE problem (like ML-KEM and Kyber), and it uses a different flavor of FO-transform to produce a KEM from its underlying FrodoPKE public key encryption scheme. It was a NIST PQC candidate KEM and is a proposed ISO standard.

FrodoKEM hashes in its encapsulation key (PK) and its ciphertext (CT) into

the final internal hashing step that produces the final shared secret

(K). Even without looking at the underlying PKE scheme, we can see it has

MAL-BIND-K-PK, MAL-BIND-K,CT-PK, MAL-BIND-K-CT, and MAL-BIND-PK,K-CT

security. Since it’s an implicitly rejecting KEM, it does not have any

X-BIND-CT-K or X-BIND-CT-PK binding properties. Easy-peasy.

FrodoKEM FO-transform IND-CCA construction

FrodoKEM FO-transform IND-CCA construction

How do I hold it?

In terms of binding properties, FrodoKEM is pretty great. In general, I still would commit to all the public transcript data in my KDF, along with the shared secret produced by FrodoKEM, but not because the shared secret is not bound to the FrodoKEM encapsulation key or ciphertext but for other protocol security properties.

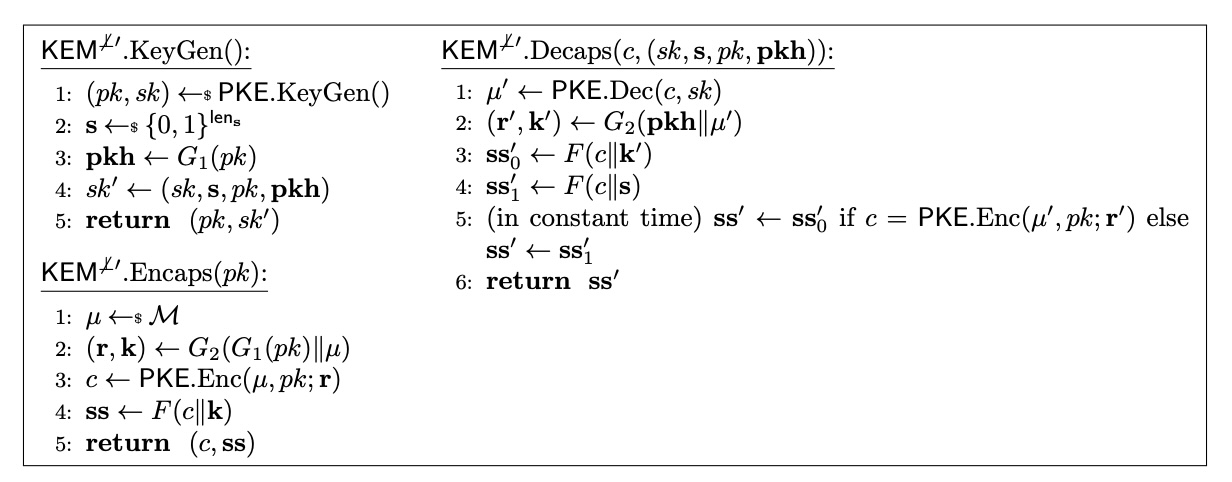

HQC

HQC (Hamming Quasi-Cyclic) is a structured code-based KEM that NIST has selected as its PQC fourth round finalist. The final FIPS standard is estimated to arrive in about two years.

NIST announced the fourth round for KEMs when they selected ML-KEM, and said they are choosing HQC “because we want to have a backup standard that is based on a different math approach than ML-KEM.”

HQC has tiny secret decapsulation keys (40 bytes), large public encapsulation keys (2.2 KB at minimum), and very large ciphertexts (4.4 KB at minimum), especially compared to ML-KEM:

HQC keys and ciphertext sizes in bytes

HQC keys and ciphertext sizes in bytes

As we saw in the journey from Kyber to ML-KEM, these numbers, the computational performance, and the exact design of HQC may change slightly before it lands as a standard in ~two years, but let’s look at the fourth round version of HQC for now.

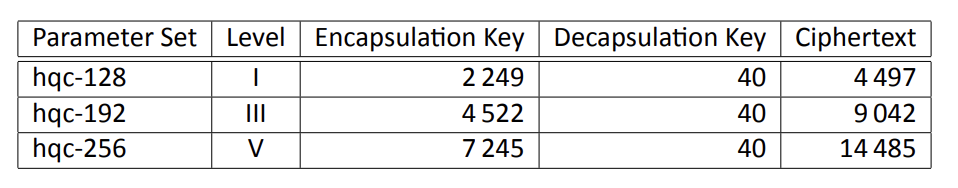

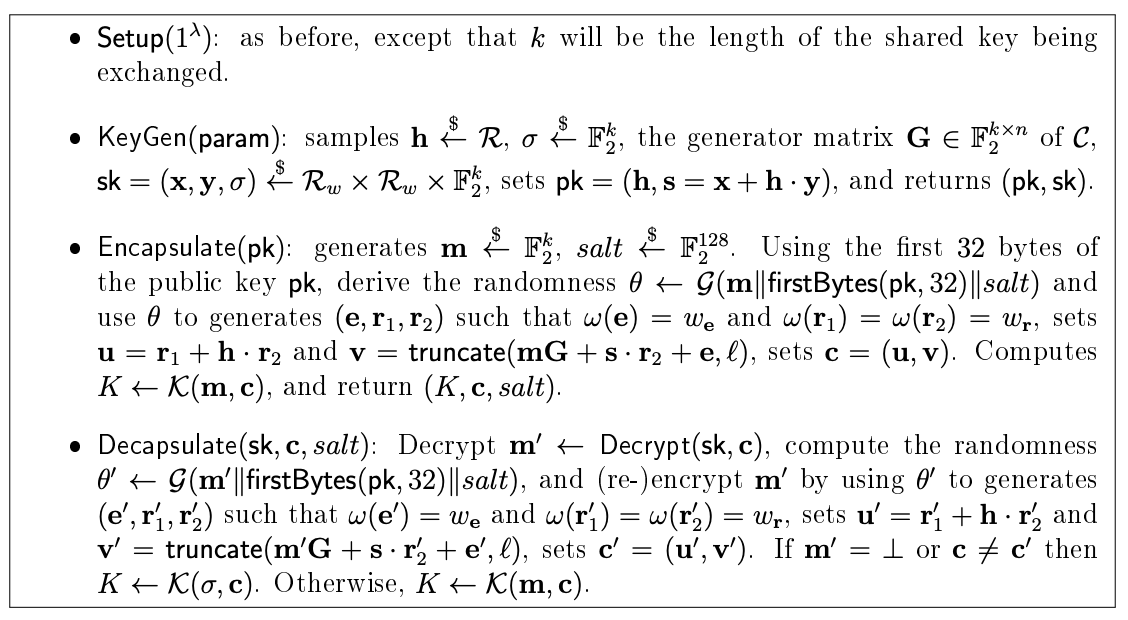

HQC KEM from Round Four Submission

HQC KEM from Round Four Submission

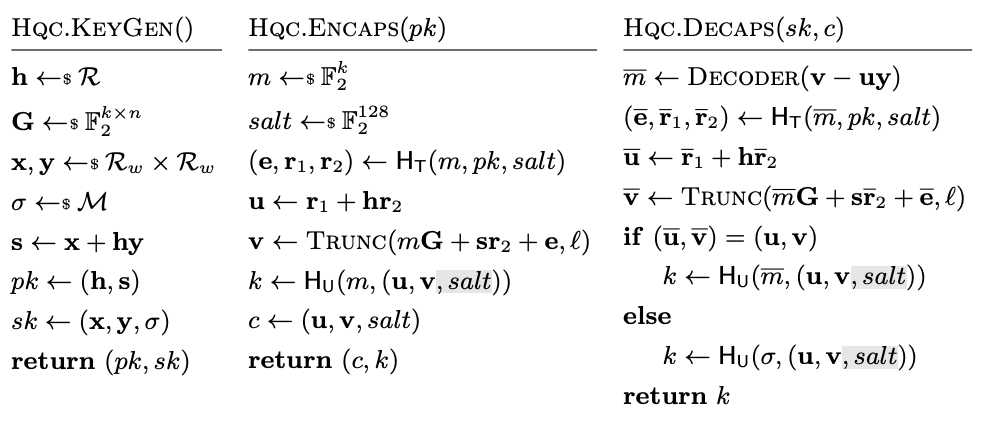

HQC KEM from Kramer, Sctruck, and Weishäupl (the grey is a suggested change, HQC*)

HQC KEM from Kramer, Sctruck, and Weishäupl (the grey is a suggested change, HQC*)

A quick look at the construction shows that HQC applies a variant of the

implicit-rejection FO transform to its public key encryption scheme to

produce an IND-CCA KEM, introducing a random salt to protect against

multi-ciphertext attacks. The salt is appended to the PKE ciphertext, and is

an input to the PKE internal KDF, but it is not part of the KEM key

derivation, and left in the clear appended to the ciphertext and output by

the KEM encapsulation. This is a signal that the shared secret K does not

fully bind the ciphertext CT for HQC.

More formally, HQC’s PKE scheme is non-rigid, allowing two

different honestly-generated keypairs to fail to decrypt with one keypair a

randomly chosen message encrypted by the other keypair with overwhelming

probability. This sounds like a good thing, until you make that

‘random message’ the implicit-rejection value of one KEM keypair and try

decapsulation under another— in the HQC construction, this results in the

same KEM shared secret K even though the PKE scheme rejects the ciphertext

because it is non-rigid. Thus, you can get the same K for different PKs,

making it vulnerable to a LEAK attacker (we did not modify any

honestly-generated keys, we twiddled with what ‘random’ message was being

encrypted). Specifically this means HQC is NOT LEAK-BIND-K,CT-PK-secure,

which implies that it is not

LEAK-BIND-K-PK-secure either.

Relatedly, the public encapsulation key is only computed over by the

underlying HQC PKE scheme, so the particulars of the PKE construction

completely determine if the shared secret K binds the public encapsulation

key PK. If the KEM KDF had included the PK directly in its preimage, this

wouldn’t be the case.

For the ciphertext binding, one can use a similar attack leveraging those

salts to show that the shared secret K does not uniquely bind the

ciphertext CT. If we use another key’s implicit-rejection value as our

‘random’ message for the PKE encryption, and change the random salt value, we

can create a separate invalid ciphertext— since the salt is not used to

derive K, the valid and invalid ciphertexts result in the same key,

violating LEAK-BIND-K-CT security.

Therefore HQC as currently specified in the Round Four submission is not

MAL-BIND-K-PK nor LEAK-BIND-K-PK, nor MAL-BIND-K-CT or

LEAK-BIND-K-PK— it is only HON-BIND-secure across the board. Considering

the sizes of the ciphertexts especially but also the public encapsulation

keys, this isn’t great.

Turns out this intitial analysis missed something, in that if you give HQC

two invalid ciphertexts (as allowed by IND-CCA) that only differ in the salt,

it will produce the same shared secret (by implict-rejection.) This means

that HQC isn’t even HON-BIND-K,PK-CT nor HON-BIND-K-CT secure!

Therefore HQC as currently specified in the Round Four submission is not

MAL-BIND-K-PK nor LEAK-BIND-K-PK, nor MAL-BIND-K-CT or LEAK-BIND-K-CT

or HON-BIND-K-CT: it is only HON-BIND-K-PK-secure, and that’s

it. Considering the sizes of the ciphertexts especially but also the public

encapsulation keys, this isn’t great.

How do I hold it?

Since HQC does not have even LEAK-BIND-K-PK security, the public HQC

encapsulation keys MUST be included in your higher-level

protocol’s KDF or key derivation. Your only protection is that secret

decapsulation keys never leak, for any reason. I would not use HQC in

practice unless I can directly include the public encapsulation keys in my

KDF or key schedule, despite their large sizes.

Because HQC isn’t even HON-BIND-K-CT-secure, the even larger ciphertexts

MUST be included in protocol KDFs or key derivation. HQC

permits everyone to do everything correctly and honestly and the shared

secret will still not bind to the ciphertext. I would not use HQC in practice

unless I can directly include the ciphertexts in my KDF or key schedule,

despite their large sizes.

If there are changes between the round four specification and the final standard maybe this will change.

Updated March 19 2025 for updated HQC round 4 candidate analysis.